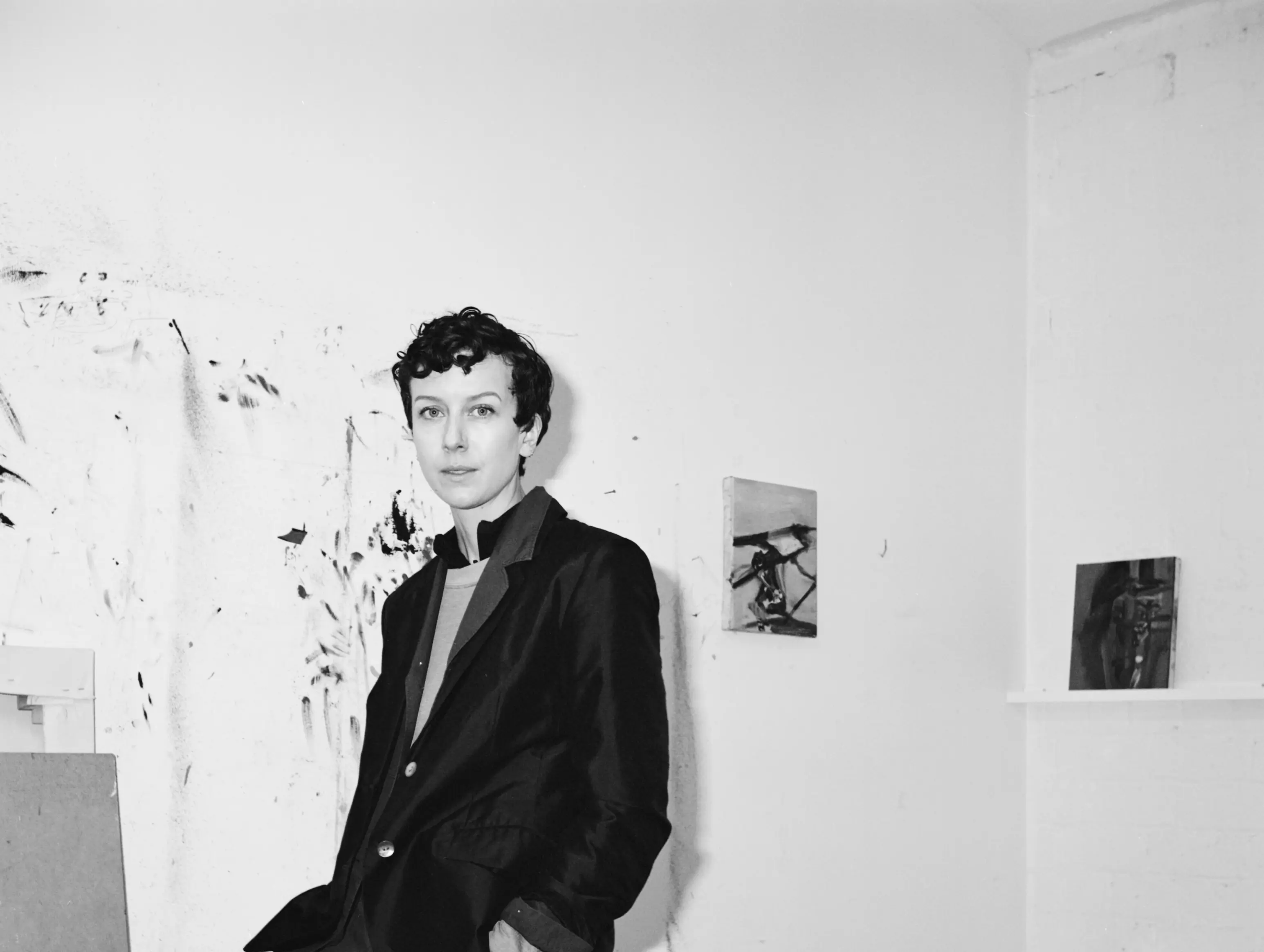

Interview with Amelia Barratt

"Associative Tumbles and Imaginative Leaps"

Amelia Barratt was born in Reading, UK in 1989 and lives and works in Glasgow, Scotland, where she works in painting, writing and performance. On the occasion of her solo exhibition at the William Hine Gallery in London, she spoke to kennich Magazine about her new series, Cut Wire: This body of work explores the performative relationship between artist, material and surface, with each abstract, often intimate composition reflecting the resolution of tensions inherent in the painting process.

Your paintings balance intentionality with serendipity. How do you know when a piece is finished?

A finished painting is a painting that I never could have expected. It’s a rare feeling that I’m looking for all the time. I have my way in but there is no formula to the way out. I would be bored if I knew what was coming. The short answer is ‘you just know’, which for me means that it bothers me. I am thinking about it at night. A finished painting often manages oppositions. Soft and hard, quick and slow. It can appear harmonious and inevitable as well as tricky and unknowable. It has to be generous but also hold secrets. I think these tensions can speak to people.

You often start with the canvas flat. Does this influence your physical relationship to the work?

Yes. I feel more involved. I work on a high table so my body is closer to the painting –– the middle of me and my guts. I don’t have to hold my arms out. It’s more immediate. I find it cuts out any apprehension in starting and there seems to be less of a lag between hand and eye. The canvas is never at rest; it is always being grabbed and turned around. The orientation isn’t fixed until it needs to be.

Working flat plays to my instinct for drawing and collage. I’m better connected to the surface of my mind, receiving and arranging material as on a flatbed picture plane. Rauschenberg was one of the first artists I felt that I could understand. Painting was less reachable until I met other painters.

Do you see your work as a form of storytelling, or is it more about evoking a certain mood or atmosphere?

There is a certain atmosphere across all my work, I think. I am a writer too and a few years ago I had a revelation: the way that I make a painting is pretty much the same as the way that I write a fictional text. It has a lot to do with the power of speculation, from associative tumbles and imaginative leaps. In both cases this happens in the latter part of making. I need plain reality to start with. This parallel between abstraction and fiction is very interesting to me.

Many of your source images come from ephemeral, weathered or abandoned spaces. Do you see your work as preserving or transforming these moments?

Transforming, yes. My starting position is with still life painters who are in celebration of the overlooked, seeking the force or potential in an object or piece of real life. Lots of my photos are from sites of physical work and repair, active places that I happen to catch without people in, early morning or after hours. I’m looking for detail to record, test and identify with. I work from tiny crops that are lively and strange, bursting with fuel for painting.

Are there any particular artists, writers or movements that have influenced your approach to abstraction or your choice of materials?

Lately I’ve been reflecting on the influence that my time at Glasgow School of Art had on how I’m painting now. When I was a student I was really into some of the Glasgow artists on the scene like Sue Tompkins, Hayley Tompkins and Tony Swain who were working with everyday materials and an economy of means: taking something to hand, laying it down, deliberating it, and there being a slow transformation. I still relate to this approach.

I was lucky to be in the painting department at that time, before the fire. We had regular life class and bright studios in the Mackintosh, a building designed for painters to carry huge canvases up staircases and through saloon doors. It was encouraging. Some of the fundamental things, how I stretch a canvas and the colours I mix with, are ingrained from that time.

I was taught by Carol Rhodes, an important influence for many ex-GSA students. I remember her tutorials clearly and go back to her work often. Her paintings are moving in their attentiveness and also, somehow, wry.

The title Cut Wire suggests something severed or exposed. Is this related to a sense of vulnerability or rawness in your paintings?

The title of the show is mundane but also, perhaps, dramatic. It zooms in and out, between small and big picture; the intimacy of a handheld tool and the potential power of a single gesture. It alludes to risk –– the ‘rawness’ you mention is part of that. I'm offering the stance that in painting, something's got to be at stake.