Interview with Hettie Inniss

Involuntary Memories

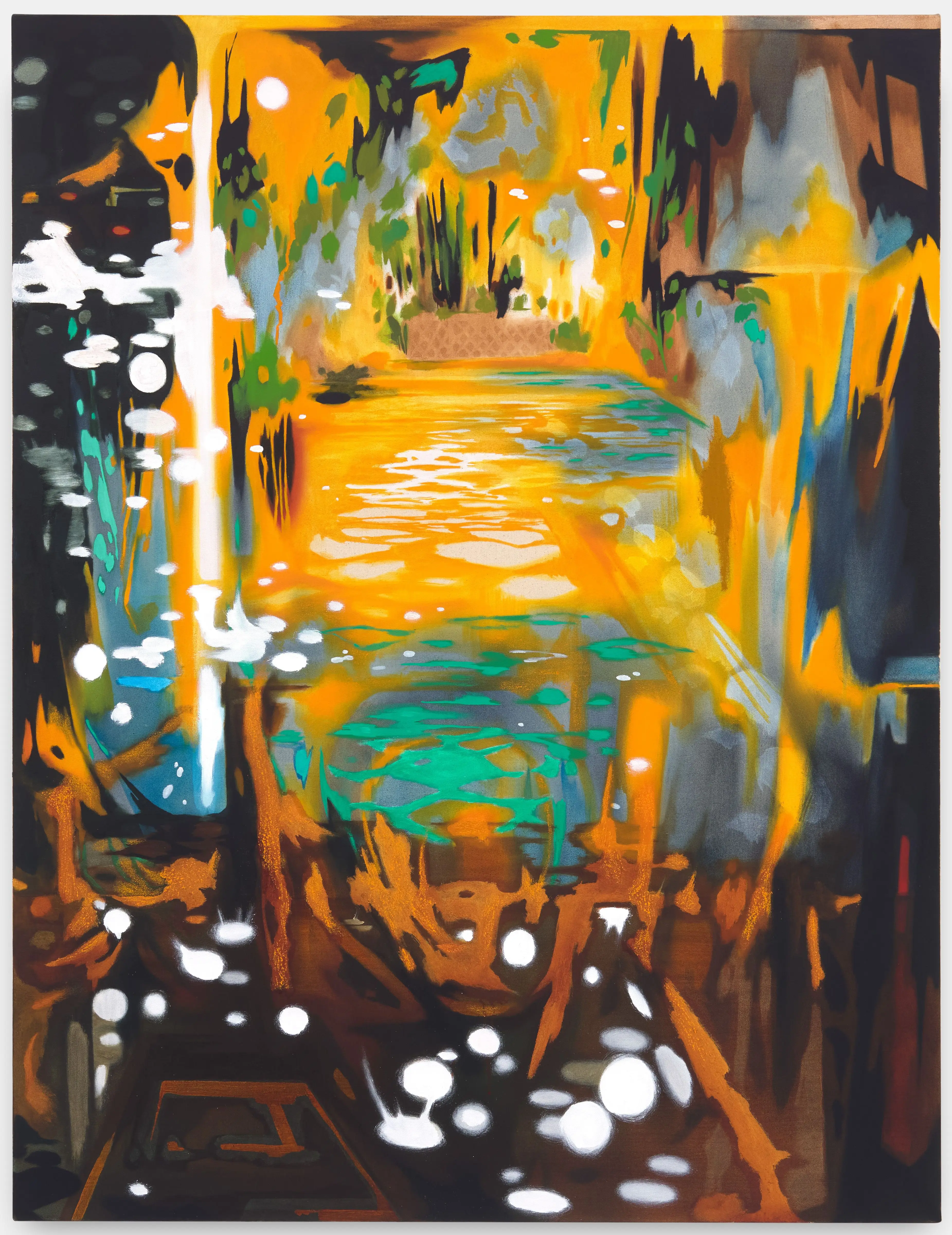

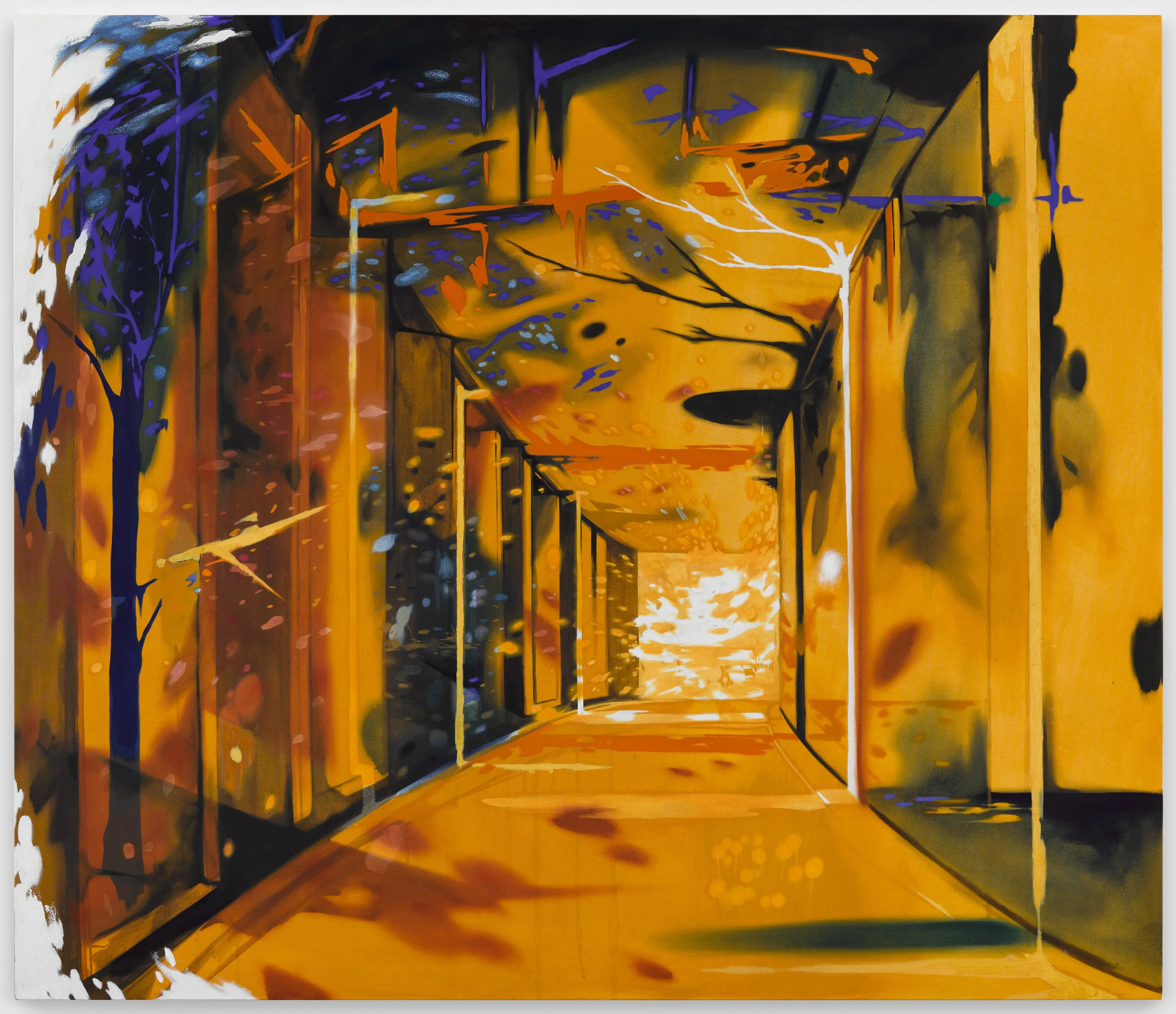

Animated by her involuntary memories, British Caribbean artist Hettie Inniss takes a Proustian approach to making, focusing on the unexpected moments when our senses are stimulated, and the mind transports us to familiar or uncanny spaces. Sitting down with kennich, the 24-year-old talks about how she seeks to create spaces by manipulating the physics, truths, and multidimensional perspectives of her canvases, allowing her to uniquely articulate the entangled act of remembering.

You work with a certain kind of painterly layering that constructs places that seem both autonomous and inviting. Do your paintings require the viewer to rely on the work's emotional agency or to actively navigate them? In a more archaeological way, so to speak?

They require the viewer to engage with the paintings in any way they choose! I see my works as environments that cannot be fixed. They can be read and understood in different ways by different people. I do not wish to control the way the audience should navigate the work; this feels counter-intuitive to my intention and philosophy behind the work. I encourage viewers to take their time with the paintings and explore the various dialogues and layers on its surface in their own way. As with memory, it is what we see in it ourselves that makes it wonderful and intriguing.

The layering effect created on the compositions provides moments of clarity, ambiguity and absence. These moments of familiarity or clarity form the ‘hooks’ of the landscape. When investigating the paintings further, we lose ourselves to ambiguity and the unknown, before finding another element to latch onto. This act of losing, finding and losing once more is the journey within these paintings.

Throughout our lives, we learn to remember in a unique way. As a result, our understanding of memory is often muddled and polymorphic. It is classically defined as something individual to which we have undivided ownership. But it can also be collective, enforced, transformed and falsified by external influences. What forms of memory are reflected in your paintings, and how does their representation relate to autobiographical memory?

My paintings are inspired by my involuntary memories. Moments of anachronism stimulated through smell. When initially engaging with memory within my practice, remembering was concerned with seeking truth. It was accessed through carefully crafted voluntary means where I would stand in my desired space, and recall an environment of my choosing, before sketching from my recollections. I would ask myself questions with binary answers: ‘was that person’s hat blue or green?’, ‘was there a car there, yes, or no?’. Involuntary memory, on the other hand, provides experiences that feel out of control, like an emotional and visual whiplash where one is entirely consumed by a memory. These memories were stimulated through the senses, predominantly smell. It is a way to access to the realm of memory and a richer landscape from which to excavate compositions. Moments from the past overlap with ones of the present to create new spaces and dimensions outside of our own. I like to call this realm the ‘floating world’.

When I paint using involuntary memory, I am also engaging with the performance of memory. The areas of the mind that are hard to pin down and difficult to understand allow for the performance of memory to take over. Much like the mind does, I too fill in these gaps with whatever marks I see fit. Although I am handling autobiographical material from my past and present, I use it to build new worlds and realities outside of my timeline. It does not aim to represent my past and it does not aim to represent it with accuracy. The practice feels unrestrictive this way.

Given your unique approach to painting, exploring the physicality and absence of memory and identity, could you discuss your technical process? How do you decide when a work is finished?

The work begins outside the studio. I have created a meditative practice that requires an urgency for slowness. When collecting and archiving involuntary memories, I must be receptive to these experiences. If I am in a state of unrest, it becomes challenging to acknowledge or remember these moments and the archive dries up. Sketching from this archive comes next. These drawings form the skeletons of the initial compositions. However, just like memory, these images warp and transform when transferred to canvas. I am able to tap into the performance of memory here and the act of painting feels more subconscious in its behaviour. Breath is important in my work. I often reach a point with my paintings where it becomes a dance of push and pull. As there are several environments in dialogue with one another, light and shade become essential towards the end of finishing a painting to return balance to the work. This process can take time depending on many factors. If I am unsure if it is finished, I turn the canvas around and return to it when I feel ready. I will know after having a break from it if it is done.

The stories of your father's childhood and the Windrush generation have deeply influenced the project for which you won the Berkofsky Art Award. How do you navigate the balance between personal narrative and wider social commentary in your work?

I believe that I can speak to personal truths within my work. When exploring the memories of my father it is through the ones he has shared with me. I bring them to life through my own lens and memories of stories he told me growing up. Community can be created through shared and or similar experiences, therefore I believe how my work touches upon wider social commentary is in the hands of the audience more so than my own. I do not aim to speak for others, I believe that there is a degree of arrogance in this. What I can do is bring attention to the way I see the world and how the world sees me. The community and connections that form from this are out of my hands but are none the less a joy to experience.

You've mentioned a desire to move beyond Eurocentric representations and decolonise practices within the art and design industries. Can you discuss some of the strategies or approaches you've used to challenge the canon in your work?

I believe that speaking to the fluidity of the black body within my work is a means of critiquing binary representations in the canon. Figures do not exist in my paintings in the conventional sense. The body is there; however it bleeds through in the fleshy undertones of the work and the use of light and shade. I aim to show the imprint and vastness of humanity through my work.

The Tate Collective has commissioned you to make a work in response to their collection. Could you give us some insight into what inspired your piece and how it relates to the work you responded to?

For the Tate Collective commission, I decided to respond to Paul Maheke’s ‘Mutual Survival, Lorde’s Manifesto’ (2015). This was an installation piece that I discovered through my sense of touch and sound. Interestingly, when walking through Tate Britain I felt Maheke’s work before I saw it. The vibrations from the speaker on the ground and the hum of the base triggered a lot of memories. Not only this, but my recognition of the base as ‘Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe’ by Kendrick Lamar, also created a rich landscape of images for me to work from in that moment. It was important for me to have a sensorial trigger from a work in the Tate’s collection in order to create work from it. This process allows me to have access to the realm of memory which Maheke’s piece provided. ‘Mutual Survival, Lorde’s Manifesto’ not only engages with a visual language but also touch and sound. As a sensory-driven artist, this became the perfect piece to respond to through my method of making.

Finally, as a recent graduate who has already made significant strides in your career, what advice would you give to emerging artists trying to find their voice and place in the art world?

I believe I am still on a journey to develop and evolve and hope I always will be. However, advice that has stuck with me is to be honest with what you want and be bold – both with paint and within the self. Community is also important. Having those around you to ask questions and to receive feedback from is an amazing catalyst for progression within the practice. It’s amazing to support one another. Look for scholarships and bursaries! I have only been able to access higher education through scholarships both in my BA and Master’s! Also, I try to embody both my mother’s drive and father’s optimistic tendencies. His philosophy is that ‘things will work themselves out no matter what form they take.’ It’s a reassuring sentiment in a space full of uncertainty and instability.